|

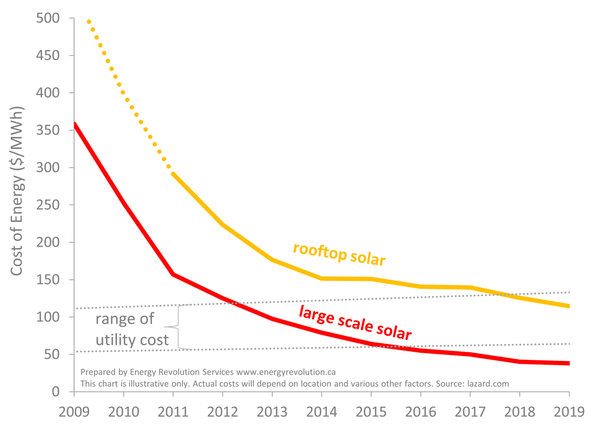

Michael Pullinger New technologies are revolutionizing the world of energy. The sight of a majestic wind turbine on the horizon can be an inspiring demonstration of our strides towards a cleaner future. But renewable energy takes many forms. Building owners can be much more than spectators. Why Bring Renewable Energy to Buildings? A building owner’s interest could be anything from reducing energy costs to leaving a positive environmental legacy. For many of our building clients, we encourage them to consider energy conservation opportunities as a first priority, as this can be one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce the operational greenhouse gas emissions from a building. But there is a limit. Once the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of energy conservation has been exhausted, renewable energy is better than reducing consumption further. If you plan carefully, it makes sense to incorporate renewable energy options that provide you with energy at a lower cost than you can buy from your utility. Renewable Electricity Before getting started, it’s worth taking a look at one of our previous blog articles “Renewable Energy – Four Things Before You Start”. That article explains some general considerations for renewable energy, including assessment of demand, resource, business case and permits. For a building-specific application, what options are available for generating your own electricity? Solar Power Solar is the best technology for building integrated renewable electricity. Solar power is simple to install and operate, low maintenance, and its cost has plummeted over the last decade. In many regions of the world, solar can now provide power to a building at a lower cost than it can be purchased from the local utility. Whether your roof is flat or sloped, most buildings can incorporate solar. While some existing buildings may have structural limitations, many of these can be managed by careful placement and design of the solar array. On a recent project of ours, a simple change in the slope of the solar panels reduced the likely snow accumulation and eliminated some major structural modifications. Whether solar makes sense for your building will depend on a site-specific analysis of the potential energy production and costs. But it should be right at the top of the list for any building considering renewable electricity. Wind Power Around a decade ago, building integrated wind power generated some interest when rooftop solar was still expensive. But it suffers from a few challenges. The wind speed is slower and more turbulent in cities due to the numerous buildings and structures that obstruct the wind’s path. The low-speed turbulent wind means a turbine in the city produces far less energy, and the stresses on the machine are higher. Small wind turbines have often suffered from high maintenance and failure rates, all of which are potentially costly and hazardous for building-mounted machines. Given all these issues, why are wind turbines such a prominent part of the energy revolution? Large wind turbines are installed at the top of tall towers, which allow them to clear the slower, turbulent wind regimes near the ground. Many utility-scale wind turbines are installed on towers 80-100 m tall, which is impractical for small turbines. Larger machines can be built and installed more cost effectively and are typically placed in locations with the best wind energy resource, such as the prairies or coastal areas. Large scale wind turbines are an excellent technology, and we have completed grid-scale wind energy studies for several clients. But, apart from off-grid applications, small wind turbines usually aren’t worth the trouble. Building-integrated installations are even more problematic. If you’re interested in building-integrated renewable electricity, you’re better off saving your roof space for solar panels. Other Options for Building Integrated Renewable Electricity? Are any other renewable energy technologies suitable for a building? Hydro and geothermal are two prominent renewable technologies, but how do they stack up in a building application? I once saw a suggestion for collecting rainwater from the rooftop and running it through a small hydro turbine in one of the downspouts. Hydro has been a useful technology for decades, but to produce a useful amount of power, it relies on the channelling of rainwater from huge areas of land. For a typical four-storey Vancouver condo building, the best we could hope for would be a system that delivered an average of 4-5 W of power. In reality, the energy would come in short bursts that are difficult to manage and fully capture. We could get the same energy benefit from changing a fraction of a single light bulb. Not appropriate for a building. For geothermal energy, there is an important distinction between geothermal electricity and geothermal heat. While it is technically possible to create electricity from any heat source, you might be better off using this for heating than electricity. Read on below. Renewable Heat When asked to think of renewable energy, many of us invariably picture solar panels or wind turbines. Electricity is important, but it’s not the only place we use energy. For buildings, it is critical to consider the energy we use for heating. It so happens that there are great options for heating with renewable energy. Heat Pumps Are heat pumps a source of renewable energy? There is some debate, but we argue that they can be, depending on how we do our accounting. Heat pumps work as an air-conditioner in reverse. Instead of cooling the indoors, we cool the outdoors, and take the heat we ‘removed’ from the outdoors and put into a building. Heat pumps allow us to push heat ‘up hill’ from a cold space to a warm space. So why wouldn’t this be considered renewable energy? Much like in a household refrigerator, we need to run a compressor to move heat against the temperature gradient. For every unit of electricity we put into the heat pump’s compressor, we are able to extract anywhere from two to four times (or more) energy from either the air, a water source, or even the ground in the case of a geothermal (ground-source) heat pump application. While the electricity may not be renewable, the heat extracted from the air or ground certainly is. The caveat is that we cannot ‘double count’ the energy. If we consider heat pumps to be a renewable energy source, then we can’t account for it on the energy conservation side of the ledger. Regardless of what we call it, heat pumps are an excellent technology and are particularly effective at cutting carbon emissions when replacing natural gas heating systems. Solar Thermal Solar heating comes in two varieties – active and passive. In active systems, solar collectors are installed on a rooftop to absorb heat from the sun and use it for heating – usually for hot water systems. This is a fantastic, mature technology, but there are trade-offs. The biggest is that you’re using up some of your roof space, which in some cases may be better left for panels for solar power. The decision will depend on your specific goals, and the relative cost of heating compared to electricity in your building. Passive solar design makes use of the careful choice of window placement, shading, building orientation and materials to optimize the sun’s energy for heating the building. The earlier you engage passive solar design considerations into your project (through simulation modelling for example), the easier it is to maximize its potential. While heat from the sun’s rays is certainly renewable, passive solar is usually considered an energy conservation solution since we typically measure its effect through a reduction in heating requirements. Nevertheless, passive solar should always be part of an overall energy plan, particularly for new buildings. What About Biomass and Waste Heat? Bioenergy is commonly considered a source of renewable energy, but using a blanket ‘renewable’ label for all biomass is controversial. The sustainability of the specific source of biomass, and how the carbon emissions are accounted for can all impact whether it should truly be considered renewable. Many sources of biomass still have an important place in the energy transition. We encourage thinking of biomass as a waste reduction process (whether agricultural, forestry, or municipal waste) rather than an energy source. While we should strive to minimize waste from those processes in the first place, if we are finding a use for something that would otherwise be squandered, we are still lowering our environmental footprint. Building owners should also review the relative costs and benefits of the maintenance, space requirements, and air pollution implications of biomass compared to alternative sources of heat. There are certain situations where biomass will be the right answer, but it won’t be for every building. What about waste heat? Many of the same caveats apply. While waste heat may not come from a clean source, when available it’s worth using. If not, the resource will be lost anyway. We are currently working on a concept for a greenhouse for one of our clients. The greenhouse would be located next door to a large industrial plant that uses natural gas to generate steam and produces a large stream of warm water as a by-product. Is this waste heat renewable energy? Definitely not. But, by using that waste heat, we are not adding any additional pollution to the atmosphere, and we are using a resource that would otherwise go to waste. What Next? Many buildings have already adopted substantial energy conservation measures, so how should these industry leaders continue to push the boundaries?

As the cost of renewable energy technologies keeps coming down, building owners should consider renewable energy to minimize their environmental impact and operating costs. There are several excellent technologies for grid-scale renewable energy, but many simply don’t scale down to the size of a single building very well. The clear exception is solar power. Renewable electricity gets a lot of attention, but clean sources of heating can often be just as effective for buildings. While definitions start to blur as to what exactly constitutes a renewable source of heat, several good options exist for both new building and retrofit applications. While not always considered renewable energy, utilization of waste resources such as biomass or industrial waste heat may be suitable options for some facilities. With so many options to consider, a good first step for most building owners is an energy assessment of your facility to understand the benefits and costs of the several alternatives. If you’d like to read more articles like this one, please sign up to our email newsletter.

2 Comments

Daryl Collerman

4/12/2020 06:09:46 am

Excellant article

Reply

Michael Pullinger

8/12/2020 08:48:15 pm

Thanks for reading, and I appreciate your feedback!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Web Hosting Canada

RSS Feed

RSS Feed